Private Raymond H. Stenback from Independence, Oregon, wrote his family that he had finally received orders for the war in France. “It is with deep regret that I write and tell you that I will not be home on that furlough for I am on my way across.” Like many Marines of today, Private Stenback’s 22 June 1918 letter resounded with anxiety and moxie; he was ready to “get into the fight” overseas and willing to trade more pay for the chance. “I might have backed out and could have been a sergeant in a short time here. I would rather be a buck private in the rear rank over there than a sergeant here. It is what I enlisted for.” Private Stenback’s letters were not written from a traditional Marine base such as Quantico or Mare Island; he was with the 112th Company, 8th Regiment, at Fort Crockett, near the city of Galveston, Texas!

Major Edwin McClellan said it best in The United States Marine Corps in the World War that “while the battle operations of the 4th Brigade as an infantry brigade of the 2d Division of Regulars overshadowed all others taken part in by Marine Corps personnel, those operations were by no means the only ones participated in by officers and men of the Marine Corps.” The Marines in Texas trained for war in France–or closer to home if necessary. Germany clearly had made attempts to cause discontent between Mexico and the United States, particularly when German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann sent his infamous telegram to the Mexican government in January 1917 encouraging the Mexican government to invade the U.S. and reclaim Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Germany had also resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. The threat to the U.S. from the south was very real; the Mexican government was unstable and disjointed after years of revolution, but remained a major oil producer for the Allied powers. Fort Crockett’s position on the Gulf of Mexico made it an ideal location for Marines to launch an amphibious operation into Mexico’s Tampico oil fields—one of the most crucial sources for the Allied war machine in Europe. Had the need arisen, Fort Crockett would have provided the definitive solution–United States Marines.

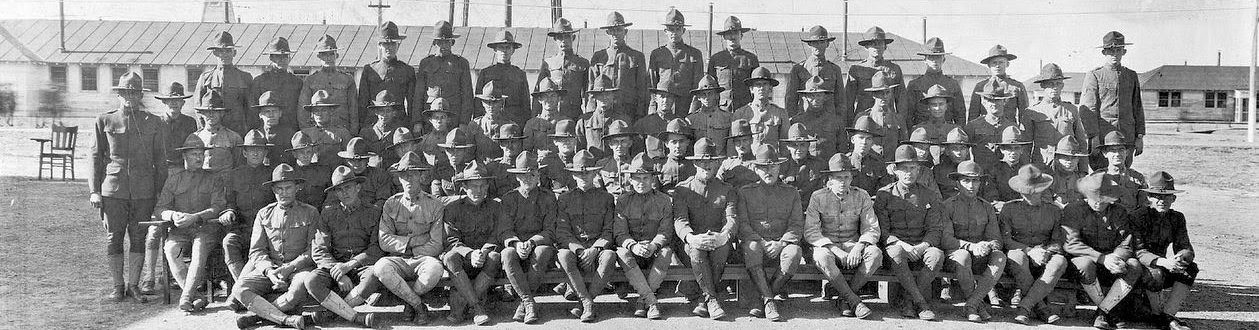

The 8th Regiment was activated at Quantico, Virginia, on 9 October 1917, and just over a month later it arrived in Galveston on board the USS Hancock, after spending a week at sea where rumors ran wild as to its final destination. None of the Marines, including Private Stenback, believed they were staying in Texas. “We arrived here at Galveston, Texas yesterday evening and have been busy unloading our necessary equipment for a short stay.” The next day the Marines were told to unload the entire ship—an all day job for nearly 1,000 pair of hands. Despite the exhaustive task, they finished the day with a four-mile march to their camp where they found level ground to pitch their tents, eat dinner, and bed down in the chilly November night.

The day-to-day life of the Marines in Galveston was consumed with learning to operate machine guns, qualifying with different weapons on the rifle range, learning flag semaphore, playing baseball games, and swimming in the Gulf of Mexico. Private Stenback kept his family well informed of the daily grind: “Signal practice has kept us pretty busy with flags, sun glasses and then one night a week we have to go out with lamps. With this system we can talk two or three miles.”

The Marines shared Fort Crockett with two regiments of U.S. Army coast artillery that were headquartered at the fort. “Talk about moss-backs—there are ever so many of these coast artillery men who have never been out of this state. They ask us what kind of a place we come from that we should have such rosy cheeks and smooth complexions.” Locals were not their only source of companionship; Stenback’s company adopted a dog that they dubbed “Rags” which apparently slept around. “Every bunk is his home when he wants to treat it as such.” Dogs were not the only mascots kept at the fort as “the company next to ours has a monkey for a mascot and it is sure a smart fellow and delights in climbing around on the fellows shoulders and hunt for something in the hair or digs down into the pockets for something to eat.”

Like their counterparts at Quantico, the Marines in Galveston kept active with sports—most notably baseball. In April 1918, the world champion Chicago White Sox soundly beat the Marines and coast artillery team. While the Marines and coast artillery played “a whale of a game, for amateurs,” they still lost 11 to 3. The Chicago Daily Tribune was more accepting than Private Stenback, who stated that it was “not any more than could be expected.”

Gossip continued to spread that the Marines would leave any day for the war in France, or Cuba (where the 9th Regiment and 3d Provisional Brigade would depart from in 1918 to join the 8th in Texas). Private Stenback even heard the speculation of “an early move to Argentina in South America to take care of threatening German uprisings and to protect American interests.” Obviously, the minds of the Marines were on the battles across the ocean and not the duty they were performing in Texas. “Things are looking pretty serious over there [France] the last few days it seems and so now it is mighty hard to tell when they will need us. I really believe we are an emergency regiment.”

With the calming of troubles in Cuba, the 3d Provisional Brigade headquarters and the 9th Regiment boarded the USS Hancock and were sent to unite with the 8th Regiment in Texas in August 1918, where they joined in the training activities and guard duty.

Private Stenback finally shipped over to France in the summer of 1918 and returned to the United States unscathed in 1919 after occupation duty in Germany. In 1971, he transcribed his letters written during World War I and turned them into a personal memoir titled, Raymond Howard Stenback as a United States Marine.

A more prominent Marine stationed at Fort Crockett during World War I had already made his mark on Mexico. Medal of Honor recipient Lieutenant Colonel George C. Reid joined the 8th Regiment in late November 1917, after a short stint at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Lieutenant Colonel Reid was aptly suited to command Marines should the need arise to land at Tampico; he earned his Medal of Honor in Mexico just three short years before during the capture of Vera Cruz. After the arrival of the 9th Regiment, he was promoted to colonel and made commanding officer of the regiment. Colonel Reid continued to serve in the Marine Corps after his duty in Texas and upon retirement in 1930, was advanced to brigadier general for having been specially commended in combat.

Another noteworthy officer arrived in Texas on board the USS Hancock with Private Stenback and the regiment in 1917. First Lieutenant Edward A. Craig of the 105th Company, 8th Regiment, lamented that he missed the “action” in France; however his time would come and fame would be his. Lieutenant General “Eddie” Craig retired in 1951 after commanding the “fire brigade” that was launched into the Pusan perimeter in the opening days of the Korean War.

On 10 April 1919, both regiments boarded the same vessel that carried them to Texas–USS Hancock—this time bound for the Philadelphia Navy Yard. No sooner had the regiments disembarked men and equipment, than they were deactivated. Although the anticipated trouble in Mexico did not materialize, one might say that the presence of the 8th Regiment and later the 9th, with the 3d Brigade headquarters, deterred any possible actions on the part of the Mexican government. Oil continued to flow to the Allied powers, and in November 1918, the war in Europe was over without an intervention into Mexico.

by Annette D. Amerman (courtesy of Fortitudine Magazine, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2008).

Regimental colors are uncased by Col Laurence H. Moses at Fort Crockett in Galveston, Texas, 1918. Col George C. Reid Papers, Gray Research Center, Quantico, VA

Signal practice at Fort Crockett, Galveston, Texas, in 1918, spelling out the familiar ”with flags. Courtesy of the Library of Congress